Jazz fans would be hard-pressed to name a more iconoclastic and unique musician than Eric Dolphy, an alto saxophonist who’s simultaneously significant and obscure. If the medium produced a jazz equivalent of Jimi Hendrix, it would probably be Dolphy; the spirit of his music has burned through the past 50 years, igniting and inspiring countless upstarts.

By its very nature avant-garde jazz stands at a distance from convention, but the music of Eric Dolphy (who died two weeks before the release of Out to Lunch) is even more irrepressibly experimental than most. Nearly as celebrated for his frantic oversized horn playing as for his left-field compositions, Dolphy was an outlier of the highest order among saxophonists in part because he didn’t seem to have any particular niche. He approached his instrument in many different ways – writing charts, trading fours with a rhythm section, playing long lines that wander adventurously and without clear direction, injecting bursts of high notes into a texture – depending on the needs and goals of his particular project.

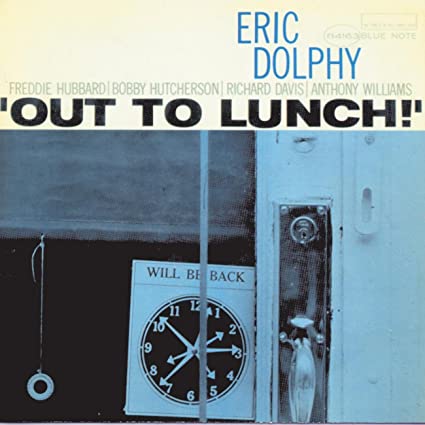

Recorded for Blue Note on February 25, 1964, Out to Lunch sounds as far ahead of its time as Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity, John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme and Andrew Hill’s Point of Departure, all of which were also recorded in ’64. Out to Lunch is widely regarded as Dolphy’s crowning achievement, and that’s saying something given the esteem he’s held in by so many. It is also one of the most significant recordings of avant-garde jazz, and a statement that remains powerful over 50 years after its release. Featuring an all-star lineup of players from around the jazz world – including trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, bassist Richard Davis, and drummer Tony Williams – it’s notable for its musical and emotional range, which is reflected in the album’s length and composition.

At a time when jazz was concerned, above all else, with the endless possibilities of free improvisation (and free dischord, free cacophony), Out to Lunch served as a shot across the bow of an entire musical establishment. It was a work that treated tradition as a challenge, melody as a springboard, and virtuosity as something to be taken at face value rather than more or less ignored.

Part of what makes Out to Lunch so striking is Dolphy’s ability to take abstractions and make them sound organic, all the while maintaining a fluent sense of melody. Amidst the sounds of sixties free jazz, the music darts in and out of phase, often times hypnotic and tense. The horns summon forth a comical collection of cartoon noises, the drums are otherworldly at times, and bassist Richard Davis had little difficulty filling up the rhythmic void any chance he got. It’s as if everyone was playing in their own little vacuum and there wasn’t any eye contact or harmonic communication amongst them to be had.

Apart from the originality of its musical thought, Out to Lunch also embodied a freer expression and spirit than any Dolphy album before it. The album’s five Dolphy originals – “Hat and Beard” (a Thelonious Monk tribute), “Something Sweet, Something Tender,” “Gazzelloni,” “Straight Up and Down” and “Out to Lunch” – embodied the precision of his ensemble performances while simultaneously exuding the limitless freedom he granted his sidemen.

Ultimately, Out to Lunch is still one of the greatest free jazz albums ever released. While the genre certainly has its detractors, those looking for an introduction to the form should look no further. Dolphy’s innovative approach to the alto sax as a solo instrument helps set it apart from his contemporaries and peers. For a free jazz record, it may not be as groundbreaking or even as accessible as some other works from the peers of Eric Dolphy, but Out to Lunch is nonetheless an important text in the avant-garde canon and an album that will continue to reward adventurous listeners.