The pianist who, for his time with Miles Davis in the ’60s, pioneered melodies and employed delicate textures to build massive pictures out of what seemed to be fractions of simple chords; the composer whose music returned jazz rhythm full circle to its African roots and beyond; the versatile and resourceful virtuoso whose career stretches from the 1960s to his own electric bands in the ’70s and beyond: Herbie Hancock is all these things.

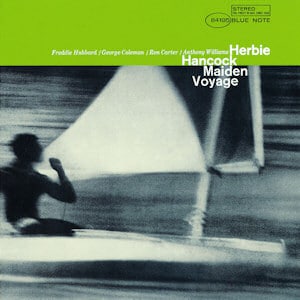

Herbie Hancock crafted Maiden Voyage as a follow-up to his excellent Empyrean Isles (1964). It marked Hancock’s fifth record as a bandleader and his fifth for Blue Note, and stood out from its predecessor as it leaned less towards the avant-garde side of hard bop and more towards conventional straight-ahead modal jazz. Featuring Miles Davis’ rhythm section of Ron Carter on bass and Tony Williams on drums, along with Freddie Hubbard on trumpet and George Coleman on tenor saxophone, Maiden Voyage was perhaps the finest Herbie Hancock album on Blue Note, showcasing his wide-ranging talents as a composer and pianist.

Maiden Voyage is a record that takes the lessons of Herbie’s time in Miles Davis’s band and puts them on display. Of course, all of this isn’t to say that Maiden Voyage is simply derivative of Davis—far from it. It’s an imaginative work in its own right, with Hancock and Hubbard emerging as the stars on a surprisingly difficult program. In many ways, Maiden Voyage is both accessible yet adventurous—and it’s a well-rounded testament to Herbie Hancock’s early genius.

Hancock’s compositions show that they had matured significantly since his earlier recordings as a bandleader. The title track is one of Hancock’s best known compositions; its melody is a siren call that lures you into its depths. “Dolphin Dance” is another one of Hancock’s finest pieces, shimmering with beautiful melody and suspended chords. “Survival of the Fittest” shows that Hancock could also handle modal jazz with the best of them.

Maiden Voyage turns 57 today. That’s old for music, but in this case, it doesn’t feel that way. Though outpaced by successive Herbie Hancock albums in terms of production and technology, it has survived the same way masterpieces often do: by connecting with listeners on a gut level. Each listen reveals new textures or surprises, or shed further light on its protagonists’ collective genius. It’s one of those records that sounds like no other, and yet feels familiar and effortless.

Listen on Apple Music

Listen on Spotify